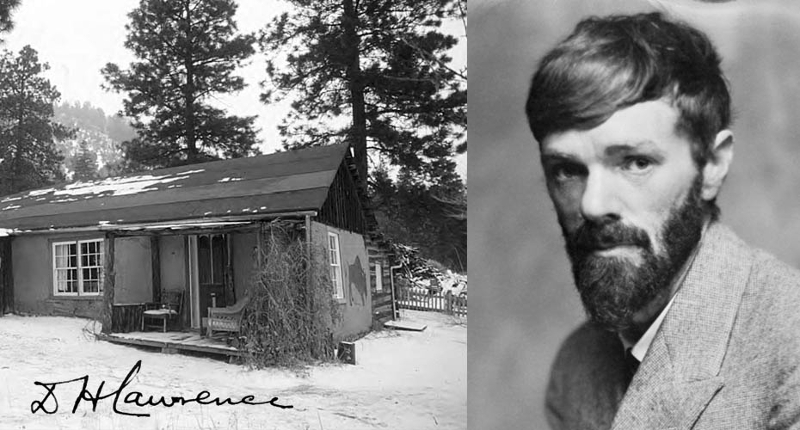

Few students know about the cultural, historical and environmental goldmine the University of New Mexico owns just outside the Taos valley — the ranch and 160 acres of adjacent land that once belonged to famous literary figure D.H. Lawrence.

Lawrence is an English novelist and painter, best known for the boundary-breaking content of his infamous novel, “Lady Chatterley’s Lover.”

Lawrence obtained the property in 1924 when his wife, Frieda, traded the manuscript of another one of his novels, “Sons and Lovers,” for the deed to the ranch. Together they spent roughly 11 months in Taos, and Lawrence passed away from tuberculosis a few years later. Frieda owned and frequented the ranch for another 25 years.

Over these years, she hosted artists and writers such as Aldous Huxley, Tennessee Williams, Georgia O’Keefe and Ansel Adams, all drawn to the area that inspired Lawrence.

“Curious as it may sound, it was New Mexico that liberated me from the present era of civilization, the great era of material and mechanical development,” he wrote.

When Frieda passed in 1955, she left the ranch to the University of New Mexico with the condition that the property “be used for educational, cultural, charitable and recreational purposes” — and for many years, it was.

From 1955 to 2008 the ranch received hundreds of thousands of visitors from around the world.

With the help of longtime caretaker, Al Bearce, a building called the Lobo Lodge was erected on the property in the 1960s. This building “slept and fed dozens of retreat and conference attendees at the Ranch for several decades” until it’s closure in 1983, according to information provided by the D.H. Lawrence Ranch Initiative.

The Peace Corps also held training events in the Lobo Lodge, and there were annual summer seminars in painting and design held there by UNM’s Fine Arts department.

In the 1950s Bearce also relocated 22 cabins, donated to him by Los Alamos National Labs, to the property. For a small expense, UNM students and faculty could rent the cabins. On holidays, like New Year’s Eve, people would gather at the ranch to enjoy the serenity of the landscape — an escape from civilization, like the one Lawrence described himself.

During this time, the ranch was the second most visited site in Taos, after the Taos Pueblo.

With the proper facilities, the property was a place where students and faculty could gather in an area of community and creative engagement.

Over the past decade though, the buildings have fallen into a state of disrepair, and the effort to keep the ranch a mecca of community and creative engagement became a downward struggle. The ranch closed altogether in 2008.

But thanks to the strong advocacy efforts made and funds raised by various D.H. Lawrence charities and the community of Taos, the property re-opened in 2014.

The funds went toward a major cleanup of the property, renovations to some of the historical buildings, as well as the implementation of a docent program. The ranch is now open to visitors on Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays.

While the historical buildings can be toured, many facilities, including the Lobo Lodge, are still in disrepair and not open to the public. Without the proper facilities, the ranch is unable to hold the seminars and courses that it once did.

In 2015, UNM creative writing professor Sharon Warner developed the D.H. Lawrence Ranch Initiatives, of which she is co-chair with Physical Plant Director Al Sena, as a means of re-envisioning the past of the ranch into the present.

“There needs to be education programming in order for UNM to justify spending money on the property,” Warner said.

The D.H. Lawrence Ranch Initiative’s current efforts are aimed at increasing funding, through UNM and outside sponsors, in order to make the necessary renovations which would enable the property to hold seminars and classes once again.

Some of these donations come from the Rananim program, a series of online classes offered to writers through UNM’s Continuing Education program. Of every tuition fee, $50 goes to the ranch.

Efforts are also being made to bring attention to and gain interest in the ranch from various UNM disciplines.

After speaking at one of the ranch’s summer seminars in 2003, UNM professor in the School of Architecture and Planning, Kramer E. Woodard, joined the effort to restore the ranch.

“We see the ranch as an enormously important resource for the University that has been in a sad state of decline, psychically,” Woodard said.

He has used the ranch as a teaching tool in many of his classes and has been part of the effort to develop a vision for the restoration.

While the historic buildings are to be renovated to their original state, as protected by the national historic registry, Woodard envisions modern facilities to replace the ones that closed.

“If the place that we imagine it to be could be realized, it would go a long way to bring back funding to the University,” he said.

Before it belonged to Lawrence, the property was once occupied by the Kiowa Indians, and there is still a trail running through the property that they used.

“We want to educate people about the importance of the Taos and Kiowa people...and involve Native Americans in the places to re-envision what happens in the ranch going forward. It’s very important to the history of the property,” Warner said.

Because of the historical context of the land, as well as the biodiversity, the ranch could be a resource for anthropology and biology departments as well.

The repairs needed for the ranch and its surrounding area include the introduction of a sustainable water source and maintenance of fire prevention plans.

“It takes a little while to get traction,” Warner said.

Warner is hopeful that with more advocacy, time and money, the ranch can return to its original state, a place where the UNM community can engage with one another on a creative level, surrounded by the beauty of the Taos valley.

Hannah Eisenberg is a culture reporter at the Daily Lobo. She can be contacted at culture@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @DailyLobo.